Community

My Home, Chernobyl: 30 Years After The Catastrophe With Alina Rudya

By Cherrie - 8 min read

Photographer @alinarudya documents her return to Prypyat, Ukraine

It was Saturday 26 April 1986 when an explosion and fire at a nuclear power plant in Chernobyl, Ukraine released radioactive contamination into the atmosphere – in huge quantities. The disaster itself, along with its long-term effects, is now considered the worst nuclear power plant accident in history. Artist and EyeEm photographer Alina Rudya’s father was working at the plant on that very evening.

Today marks 30 years since the catastrophe. We had the chance to sit down with Alina for this touching interview, in which she tells the story of how she was evacuated from nearby Prypyat at only one year old. And how, with the help of Kickstarter and the people of Prypyat, her photography project took her back to the now ghost town, time and time again.

Read on for the full interview with Alina Rudya:

By

Alina, tell us about yourself.

I’m Alina and I moved to Prypyat, Ukraine in 1985 when I was a few months old. Soon after an atomic catastrophe hit Chernobyl, a city 3 kilometers away. Along with my parents, then aged 28 and 23, I was evacuated and raised in Kiev. I later went on to study both in Berlin and in New York. In 2011, 2012, 2015 and 2016 I returned to the hometown I forced to leave – and took my camera with me.

My father was an engineer at the Chernobyl plant. In fact, he was working a night shift at the atomic plant on that very night. Our town Prypyat was built for families of the nuclear power plant employees – 50,000 residents, an average age of 26. All of whom were evacuated two days later. The fourth reactor at the plant had exploded during a test run, releasing a highly radioactive cloud into the atmosphere. It was, and still is, the worst atomic catastrophe in modern history.

And then you returned?

The catastrophe altered my parents’ lives drastically and radically – and mine too. In 2011 I revisited Prypyat for the first time since. Chernobyl is a town I never knew and never will but, in many respects, all of my desires and passions sprung from its ruins. And many people I miss are gone because of it. My father died years ago, his health ruined by his work as a scientist in radioactive environments.

Alina’s mother walks what once was the main street of now ghost town Prypyat. By

Tell us about Prypyat Mon Amour.

Prypyat Mon Amour is the project that documents my (re)immersion into what is now a ghost town – the little town that marks my life’s genesis and also, through my absence from it, my greatest influence. It’s a project about grave loss, redemption and the awakening of long forgotten memories.

When I returned in 2016, right before the 30th anniversary, my life wasn’t the central focus. It was about the lives of others, of those who were evacuated – some my age, some older, some with children of their own. All of whose lives were directly influenced by the catastrophe. I went back to Prypyat with them – back to the ground zero of our lives today.

The main theme in my work was photographing these people in their old flats and the familiar surroundings of their past. I was documenting the stories of the city they left behind.

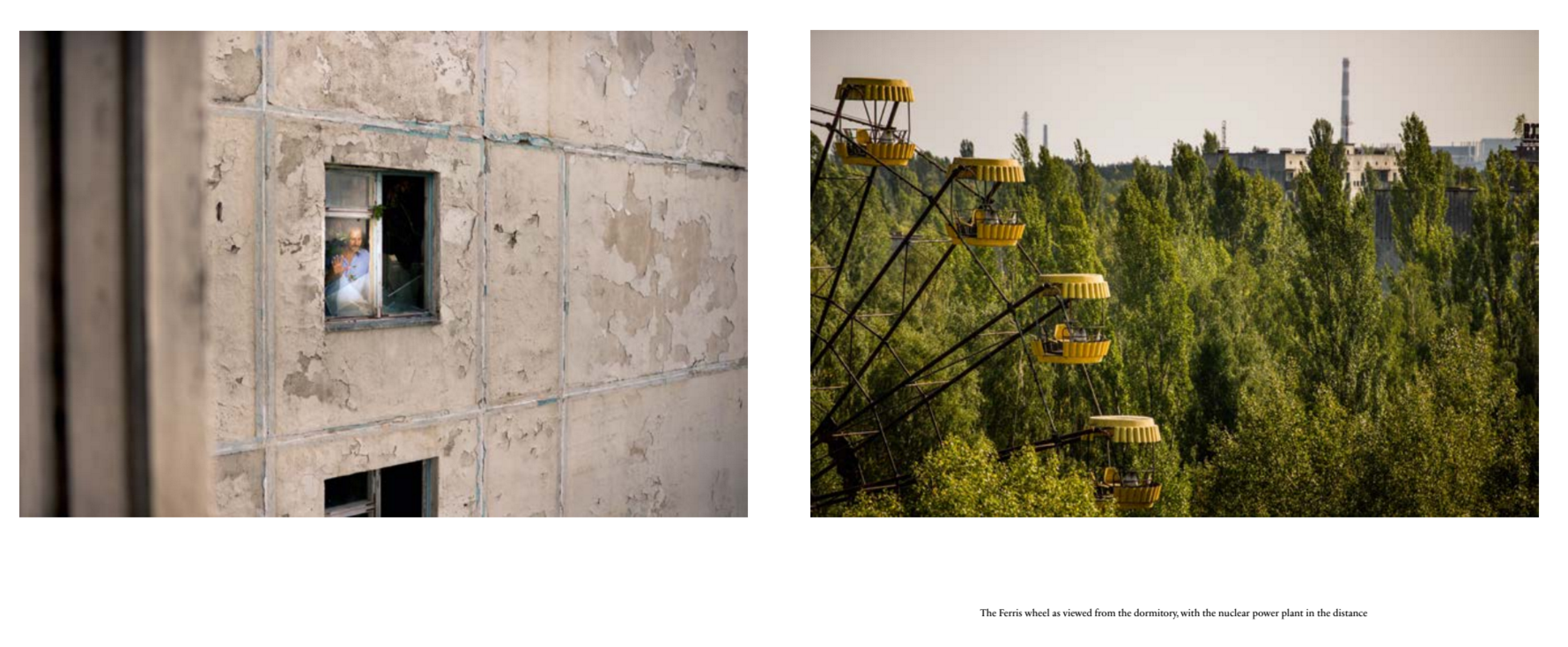

“The Ferris wheel as viewed from the dormitory, with the nuclear power plant in the distance.” – from Prypyat Mon Amour

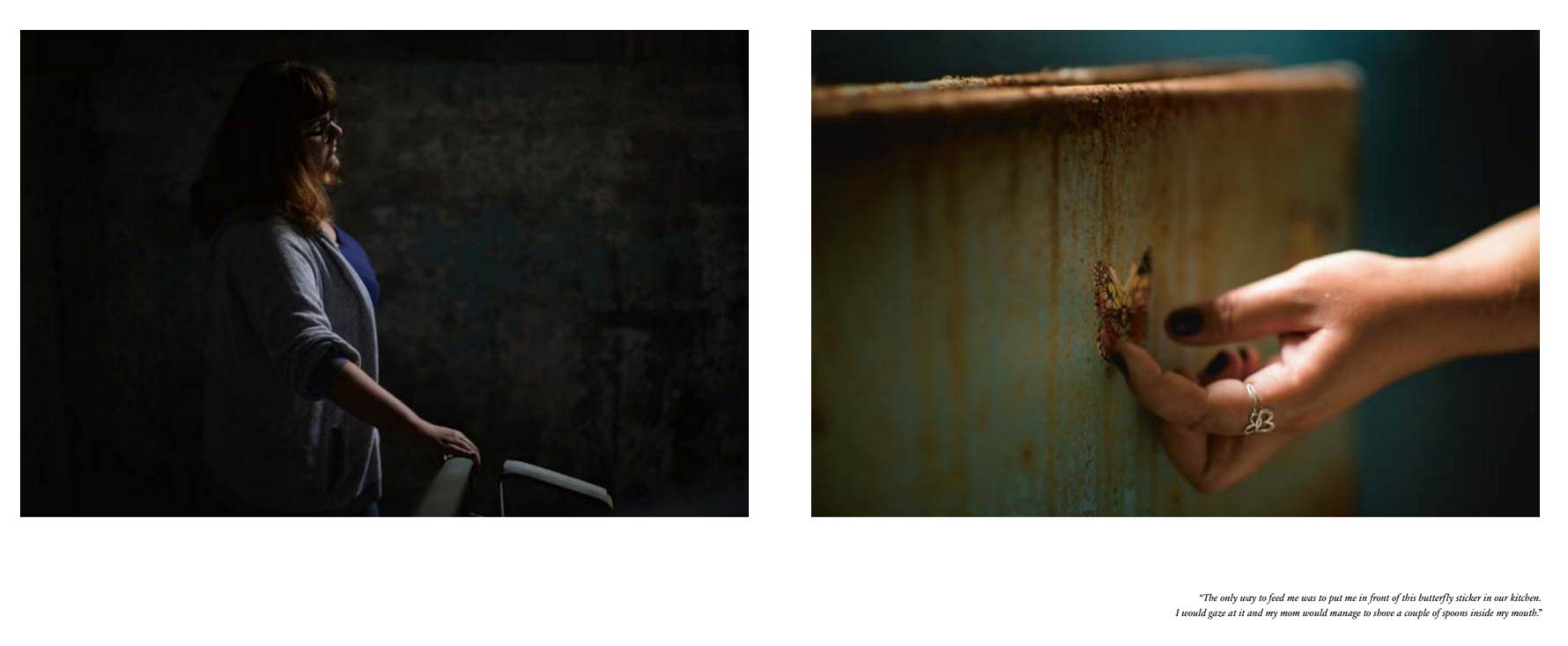

“The only way to feed me was to put me in front of this butterfly sticker in our kitchen. I would gaze at it and my mom would manage to shove a couple of spoons inside my mouth.” – Alexandra in Prypyat Mon Amour

What led to you returning again in 2015 and 2016?

I wanted to finish the series for a long time and, with the 30th anniversary approaching, I thought ‘now or never’. Financially it was difficult. I was looking for grants to let me finish the project and publish a book – and when Kickstarter came to Germany in May last year, I was one of the first ones to start a campaign there. It became a staff-pick and had good press coverage and was finally fully funded. At last I was able to finish the series.

What was the motivation behind Prypyat Mon Amour?

I am not just sharing pictures of an abandoned town – many photographers and tourists from around the world do that. Prypyat Mon Amour is about my personal journey and the story of people who, like me, were evacuated. People who lead seemingly normal lives but whose past, present and future will forever be marked by this event. I want to show the emotional nostalgia triggered by the return to their hometown. Where some of them grew up, others fell in love, got married and had children.

How was it returning to Prypyat with the people who lived there?

Of course I remember nothing of the city. Walking there with those who’d point to a piece of debris and tell me “that’s where I used to buy ice cream” or “that’s where I went to watch movies” – that really struck a chord. One women couldn’t believe her eyes when we entered the town. It was all woods. “But where is Prypyat,” she asked, and started crying.

Despite remembering little, the other ‘Kids of Chernobyl’ and I have had our lives changed by the event. Marianne Hirsch called it “post-memory”. She used the term for the children of holocaust survivors. They weren’t there but it influenced their family history so much that it became part of their own personal memory. I remember the stories of my parents, I look at the old pictures my dad took at the beach on the Prypyat river – all of these things could have been me. It could have happened to me if the accident didn’t occur.

What’s the significance of the 30th anniversary to you?

30 is a significant date in anyone’s life. It is the age when you are still young but already mature enough to realize the causes and the consequences of what happened, of your own responsibility etc. I am now old enough to see the whole picture and to form my feelings and reactions into a photograph, which would be the reflection of my inner state and my artistic answer to the tragedy.

Will you ever return to Prypyat?

Going to Prypyat over and over was psychologically exhausted. It was hard to comprehend how people I went there with lost relatives, loved ones, their lives changed. I was constantly thinking of my father and his death, of all the things that could have happened differently.

I don’t want to go to that town in the near future, but I would like to continue my exploration of the Exclusion Zone. There are still old people who lived in the abandoned villages around Chernobyl – they may not have too long left. I already took portraits of many of them and I would like to continue telling their unique stories.

“We were really happy here”. Valentina, an unpublished outtake from the series

. By

“We got married in the cafe Prypyat. Our table was in the middle of the room. Everyone was there,even two girls from Cuba.” By

Yuriy in his former school in Prypyat. By

Alina’s mother in the window of their former apartment on Lenin Avenue 17, Prypyat. By

Maria in the evacuated village of Opachichi, Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. By

By

Thank you Alina for the incredibly moving interview. Follow Alina on EyeEm to see even more of her work.

Having been published and exhibited worldwide, a monograph of Alina’s work, published by DISTANZ Verlag, is now available. She was also honored at the 2015 Android Photography Awards and will be talking to EyeEm’s Severin at a Gallery Weekend Berlin event on Saturday. In Berlin? Come say hi!

Header image by @alinarudya.